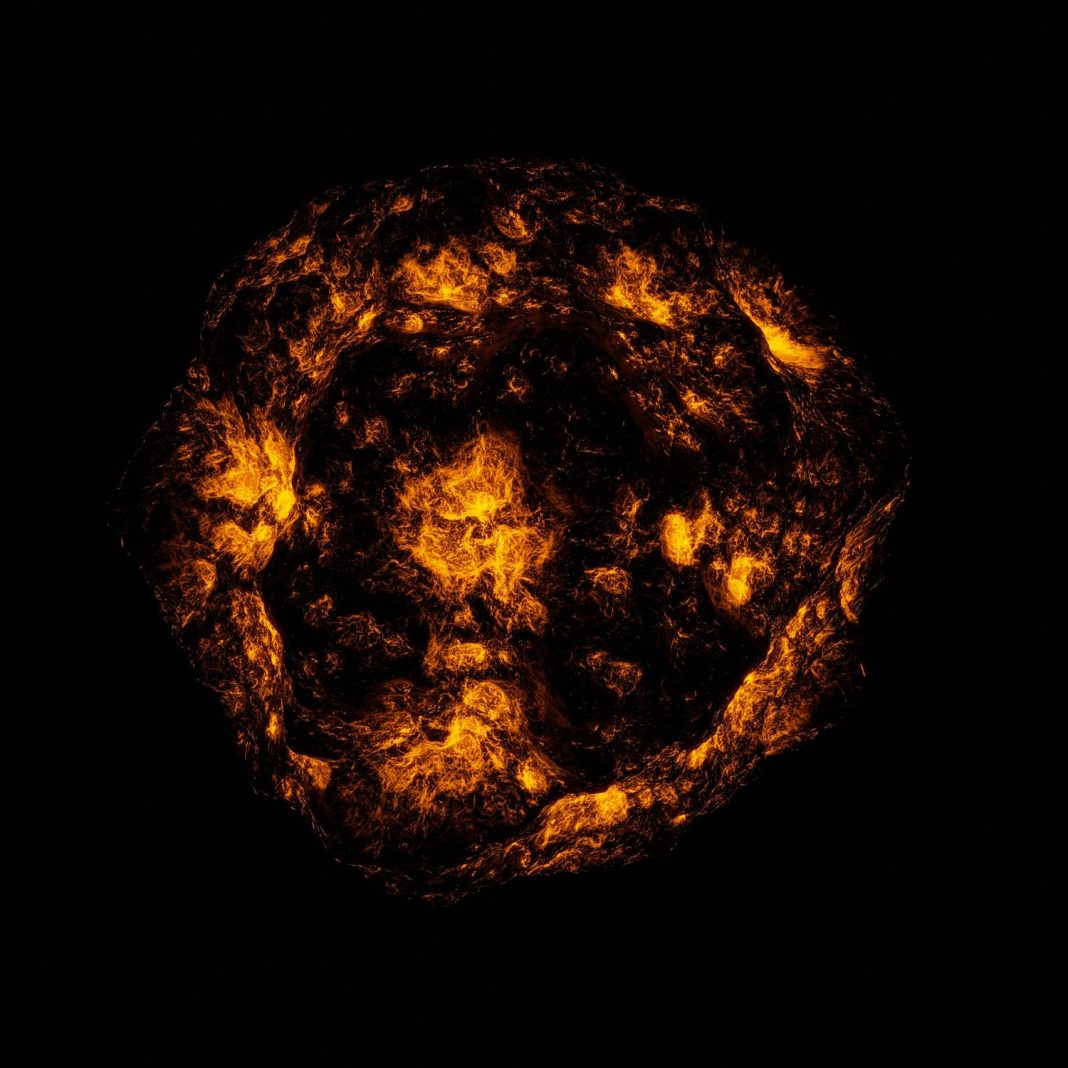

Sometimes you go against the advice of the well-known saying and choose a book by its cover. A design draws you in through color or shock; a title intrigues you. Heat + Pressure: Poems from War by Ben Weakley delivers on the initial interest brought about by its unique title that sits in bold letters over the melted green army figure on the cover. Heat + Pressure shows how today’s warriors can become poets and help veterans synthesize war and their reintegration into society. As this review argues, reintegration after war is a formative process fraught with difficult acknowledgements, depths of disillusionment, and realizing one’s own strength for creating something instead of destroying it. It also provides welcome space for reflection amongst the veteran community.

Consider the title for a moment: Heat + Pressure. Two words that cause reflection. Does one read them as “heat and pressure” or as “heat plus pressure”? The title could be the first poem of the book. This wordplay sets the tone for the rest of the collection, including the section titles. Five sections divide the book: “Heat,” “Pressure,” “Blast,” “Debris,” and “Fragmentation.” Peruse the section titles and the poems seem to tell a story of a soldier shaped, formed, and fractured—in the literal sense—by an improvised explosive device. But that’s not the whole story. Instead, a retired soldier grapples with the war-games of his youth, the boredom and chaos of his service, and the struggle to find common ground with angry citizens bent on destruction.

The first section, “Heat,” seems to be an autobiographical account of the author’s journey from child to soldier. Part of this journey involves poems about his grandparents who never talked about their wars, his own shenanigan-filled childhood, and what seems to be his father’s disappointment with his son’s immaturity. The first section ends with a familiar notion: that young people take on the narratives of their citizens calling for war and vengeance. After reading “America Calls Him,” the reader may think back to the exhortations of Paul Baumer’s schoolmaster in All Quiet on the Western Front.[1] That might be the point.

The second, third, and fourth chapters—”Pressure,” “Blast,” and “Debris”—toss away glamorous views of war. These chapters capture the boredom of 4 a.m. range days and the shock of having the meaning of the word obliterated when bombs destroy lives and material alike. Sometimes the dead are soldiers, and other times the dead are children; all are tragic and wasteful. It is in these sections that the poems introduce Musar Afghanistan, an imaginary Afghan warlord and elder who torments the poet with doublespeak during war and peace. The boring and mundane intermix with chaos and insanity. A busy nighttime patrol encounters gunshots and an opportunity for voyeurism on an Iraqi couple. A war wound turns out to be from a fall into a hole while walking with night vision devices. Such embarrassing moments are the unspoken anecdotes of combat, and convey the absurdity and vulnerability of such moments.

“Fragmentation” is perhaps the most difficult chapter. The poems speak of U.S. callousness towards migrants, the moral injury caused by the January 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol Building, and the destabilizing feelings of re-integration. The latter feelings are a constant theme in war poetry. Veterans have struggled to come back to their homes and find everything changed. What is unique about Weakley’s work is his social commentary on the lack of humanity from our fellow citizens, when he was the one supposedly managing violence on our behalf. He finds the behavior of angry insurrectionists reprehensible and sees parallels to his nemesis Musar Afghanistan, who has followed him to create battlefields on the homefront.[2]

Which brings us back to the cover of the book. The green army figurine on the front at first looks to be melted into pavement. An alternative perspective shows itself after reading Weakley’s poems; the figurine was softened by the heat of war, thrown amongst debris by many blasts, and trampled by his fellow citizens after his return home. I could not help but think of the assumptions civilians make about veterans, whether by carelessness, ignorance, or anger.