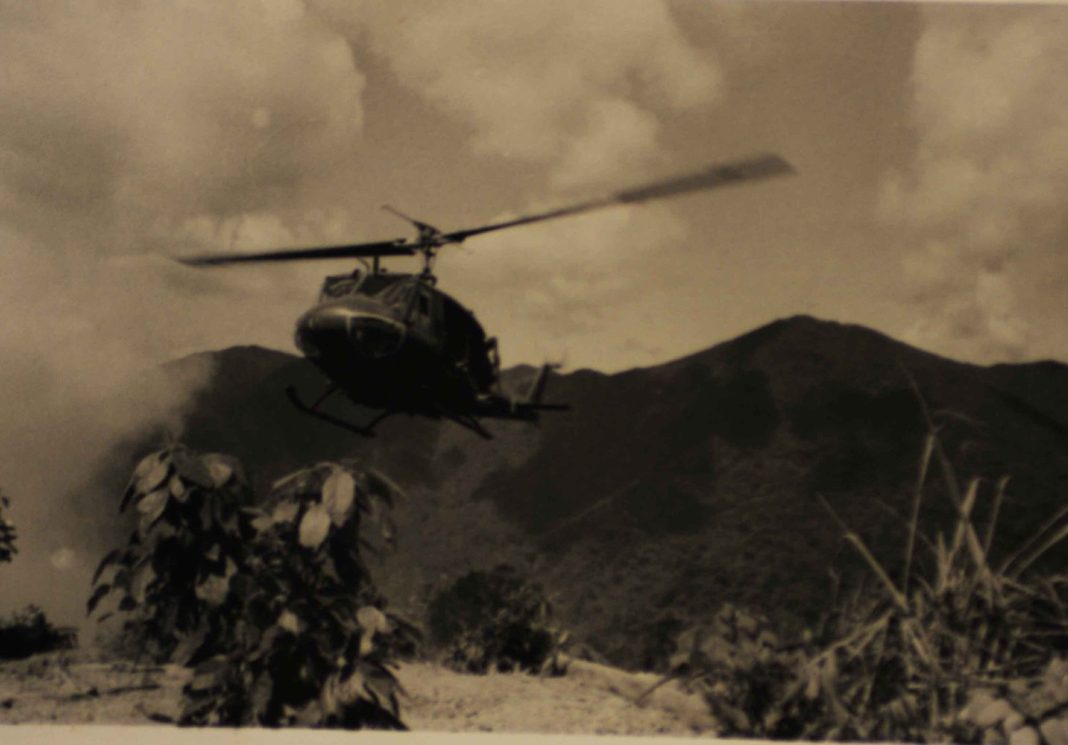

Mud Soldiers: Life in the New American Army is an examination of the post-Vietnam U.S. Army and the pre-Gulf War Army. It serves as an excellent supplement to recent works on the AVF by authors like Beth Bailey, Bernard Rostker, and William A. Taylor.[2] Author George C. Wilson writes a broad study of Charlie Company, 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment (2-16), 1st Infantry Division spanning two generations of soldiers. In the first chapter, Wilson focuses on Charlie Company in Vietnam. The author recounts the company’s actions in the battle of Xa Cam My, part of Operation Abilene, on Easter Sunday and Easter Monday in 1966. Using interviews from survivors, Wilson provides a riveting narrative over the course of the vicious battle. The battle’s appalling 80% casualty rate left 71 wounded and 36 Americans killed, including Air Force pararescueman A1C William H. Pitsenbarger and Sergeant James W. Robinson. Both earned the Medal of Honor for their actions during the battle. In one emotional scene, “[One soldier] told a friend he felt like crying but knew once he started he could never stop. So much pain. So much death. So much being alone.”[3]

The ensuing 14 chapters cover the Charlie Company of 1987-1989 as it participated in the Cohesion, Operational Readiness, and Training (COHORT) program, designed to increase unit effectiveness and cohesion by keeping soldiers together for the duration of their careers, that lasted from 1981-1995. In an easy-to-read 276 pages, Wilson explores “one of history’s ironies that the 1966 Charlie Company draftees, by sacrificing themselves so heroically and in such great numbers, helped end the draft that yanked them into the Vietnam jungle.”[4] He provides a detailed narrative, explaining daily life of a volunteer soldier in the Army of 1987-89. He follows the soldiers as they begin their Army lives first as infantry trainees in One Station Unit Training (OSUT) at Fort Moore, Georgia and then infantrymen at Fort Riley, Kansas. Wilson builds close relationships with these men and their families as they adjust to Army life in training and at their first duty station, often far from home.

Wilson was well-qualified to write this book. Spending nearly 25 years as a Washington Post defense correspondent from 1966-1990, he embedded with U.S. troops in Vietnam in 1968 and 1972. In 1983, Wilson was aboard the carrier USS John F. Kennedy during their retaliatory strikes in the aftermath of the Marine barracks bombings in Lebanon. This experience would form the basis of his 1986 book, Supercarrier: An Inside Account of Life Aboard the World’s Most Powerful Ship, the USS John F. Kennedy, which provided a detailed view of ship life from the sailor’s perspective.[5]

Mud Soldiers draws common ground between the Charlie Company soldiers of Vietnam and the Charlie Company soldiers of 1987-1989. They are all normal people, from Somewhere, America. Their life circumstances often influenced their paths to becoming soldiers. The contrast between the two companies is clear. One saw significant combat with ranks filled with volunteers and draftees. The other was filled with all volunteers whose combat experience did not extend beyond maneuvers in “the box” at the Army’s National Training Center (NTC). In highlighting these differences, Wilson shows that the “mud” is both very real when slogging around the cold Kansas prairie, and unseen in experiencing close proximity to the same people every day, loneliness, boredom, overwork, and wasted time. These layered contrasts define the mud for the men of 2-16.

Geared toward the American public, Wilson presents an unvarnished look at a junior enlisted soldier’s life in the Army of the 1980s. The author pulls no punches on how drill sergeants treated their recruits, and how soldiers treated each other. Mentorship and frustration from the drills combines with trainees’ camaraderie and bullying one another, and their ultimate admiration for their drills.

The author does not engage in a concentrated discussion on the utility of the AVF until over halfway through the book. This is a strength for a story about the AVF told through the eyes of someone in its ranks, rather than an academic study with jargon and institutional language. Wilson keeps the perspective at the junior enlisted level, an approach that is biased but also builds reader empathy for the soldiers of Charlie Company facing complicated leadership.

Wilson presents post-Vietnam attitudes, which are not too different from some contemporary discussions. In a discussion with Colonel Richard S. Siegrfeid, then commandant of the U.S. Army Infantry School, on how the AVF ought to be employed, Wilson asks about the risk of the military becoming “separated from mainstream America.” Siegfried responds that the Army of 1987 was too small to fight a war with all volunteers. A draft would need to be called and the country mobilized for war. Siegfried explains that, “A country fights a war. If it doesn’t, then we shouldn’t send an army.”[6]

For those who have served at Fort Riley, Wilson’s descriptions of the weather on the Kansas plains are vivid and memorable. Hot, humid summers give way to bitterly cold, windy, and rainy winters that cause hypothermia for one Charlie Company soldier whose platoon brought no cold weather gear to the field. Wilson uses this incident to highlight leadership failures at the company level within 2-16. Platoon leaders seemed more interested in over-training their soldiers than getting to know or spend time with them, perhaps for fear of becoming too close with them. Summarizing this attitude is a young lieutenant, commissioned at the nearby University of Kansas, who explains to Wilson, “‘What I’ve been taught is that when you’re a lieutenant you don’t have to explain your actions to soldiers. They have to do stuff without question: execute now…in combat you don’t have time to explain.’”[7] This is made worse, Wilson argues, by quick officer turnover. Junior officers have neither the experience nor the success in training to warrant further advancement on short timelines.

Wilson notes a clear divergence between junior enlisted soldiers and the company leadership, and what each thinks are the challenges in Charlie Company. Greater input from company or battalion leaders during training exercises could have offered more perspective on junior soldier performance and challenges.

Wilson is highly critical of the COHORT experiment, discovering that 15 of the 66 soldiers who had arrived from Fort Moore were gone after one year on station. A 2022 paper published by Army University Press describes the COHORT program design as a way to create “stability within the junior enlisted ranks.”[8] As Wilson showed, this was not reality in Charlie Company and a fundamental challenge to many soldiers in the unit. In chapter 12, he explores this phenomenon with Army-provided data that shows Charlie Company’s attrition of new soldiers; 17% of Charlie Company’s soldiers had attrited, compared to 12% with the rest of the Army. However, both Article 15 administrative punishments and AWOL soldiers averaged far above the rest of the COHORT Army.[9]

In Wilson’s discussion with 2-16’s command sergeant major, he reveals that many of the Army’s most effective NCOs seemed to have left the service once the AVF was instituted. This led to a lapse in effective training, particularly for an experiment like COHORT. The new generation of soldiers lacked discipline, exacerbated by weaker and more inexperienced NCOs and the apparent nothingness of a duty station like Fort Riley.[10] As one Charlie Company soldier explained, “I’d sign up for the Army [again], but not COHORT. Everybody gets tired of seeing everybody.”[11]

Wilson does recommend changes, anticipating that “the pool of young men and women to recruit [would] shrink in the 1990s.”[12] Some of these can be seen in many organizations across the military with varying results. Competition with the broader American marketplace would make recruiting more challenging, on top of the retention issues Wilson identified at Fort Riley. He recommends that officers attend basic training to better understand junior enlisted perspectives. He notes that training should be more “fun” with digital training aids. He advocates liaising with families to prevent “stonewalling” when soldiers are injured during training, and improved exit options to mitigate AWOL cases and desertion. The most interesting recommendation is a new set of promotion criteria that relies on “winning” in battles at NTC or other training centers in order to take command, lead a platoon, or stay in a key leadership role.[13]