After contracting polio and entering politics, Franklin Roosevelt needed his wife, Eleanor, to serve as his “listening post,” traveling the country and keeping him abreast with public opinion.

After he became president and World War II began, that link with the people became more essential. Eleanor Roosevelt also was more than willing to be involved in activities surrounding the military conflict.

She traveled to London in 1942 to be the president’s eyes and ears among his British allies and European governments in exile. But she wanted to do more.

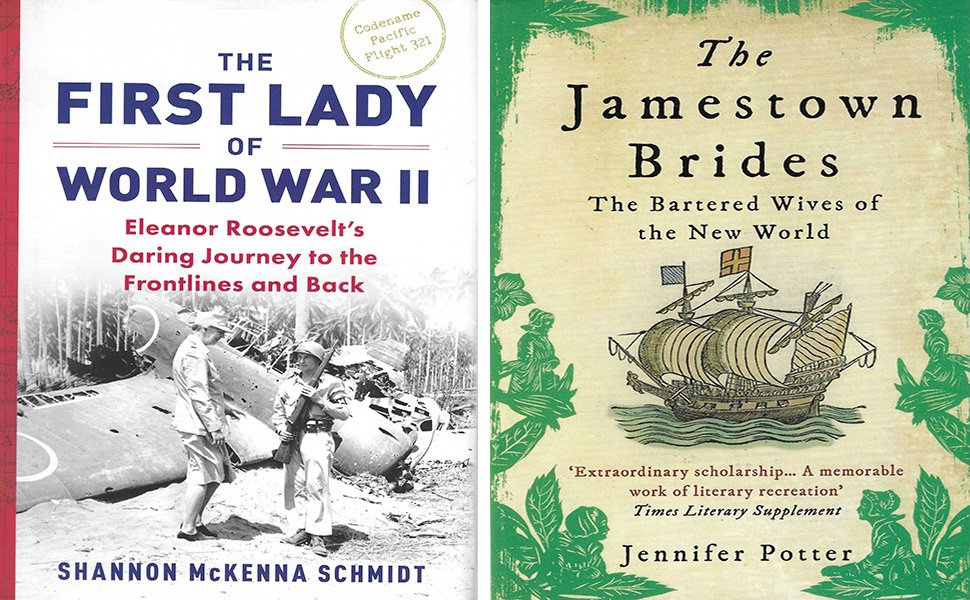

Shannon McKenna Schmidt’s newest book, “The First Lady of World War II: Eleanor Roosevelt’s Daring Journey to the Frontlines and Back” (Sourcebooks, 336 pgs., $26.99) tells an amazing story of her own battle to visit the war’s Pacific Theater of operations.

After setting the scene, Schmidt meticulously tells the story of Eleanor’s efforts to convince the president that she needed to get near the battlefields, where her four sons were already serving.

She needed to be there to provide first-hand accounts of the war. She wanted to go to Guadalcanal, first and foremost.

When Eleanor finally succeeded in getting Franklin Roosevelt to approve of the trip, she faced “near objections” from most military commanders with whom she interacted. They simply didn’t want her around.

Top of that rank was William F. “Bull” Halsey, champion of Guadalcanal who later became a five-star fleet admiral. He believed “do-gooder” Eleanor had no business in the combat theater. However, it only took a little of Eleanor’s personal courage to convince him that her presence was, in fact, doing good, as Schmidt outlines.

Eleanor’s trip takes her to from San Francisco to Hawaii, Christmas Island, New Zealand and Australia and then on into the Pacific military zone of New Caledonia, Efate, Espiritu Santo and finally Guadalcanal, her ultimate goal.

Using many new sources, Schmidt tells a travel story, taking a new approach and making it a lively saga. Always dressed in a bluish-gray hue of a Red Cross uniform with a large billed hat, Eleanor made it a requisite to visit enlisted men as well as officers at every stop, including hospital buildings and tents.

Many injured young soldiers, sailors and marines asked her to take messages back home, which she dutifully did.

The trip was from Aug. 17 until Sept. 22, 1943 — five weeks of secrecy. Her “My Day” newspaper column for the first 10 days carried a date line of Hyde Park, New York. It was not until she appeared in New Zealand, Schmidt outlines, that the press became aware she was out of the country. And no one speculated about Guadalcanal.

The fight to take the island of Guadalcanal from the Japanese was between August 1942 and February 1943 and was multi-faceted. The casualty list was startling: U.S. forces, 7,100 dead and 8,000 wounded; Japanese forces, more than 19,00 killed and an unknown number wounded.

Even though the battle had concluded months earlier, there was still a war atmosphere on the island when Eleanor visited. Schmidt notes that several times there were sounds for an “air raid” that never happened.

Schmidt notes that in her diary Eleanor wrote before she left, “Hospitals and cemeteries are closely tied together in my head on this trip.”

Jamestown Brides of 1621

When the Jamestown Colony was established in 1607, the settlers were mostly single men looking for escape and/or to get rich. The Virginia Company of London, the sponsor of the colony, soon felt it was necessary to advertise for brides to join the colonists in the new land.

Therefore, in 1621 several ships — carrying 56 women arrived at Jamestown and those females — some ultimately brides, are the focus of Jennifer Potter’s “The Jamestown Brides: The Bartered Wives of the New World,” (Atlantic Books, 384 pgs., $15.30).

Speaking via telephone from her London home about her book, Potter said, “I was intrigued by this story that women from good families (daughters of artisans and gentry) were willing to cross the Atlantic on a very dangerous journey” to become wives.

She first learned of the brides when visiting the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library in Williamsburg and read an article by historian David R. Ransome. “It’s the kind of story that really stays with you and it stayed with me. It eventually grows in your head and you reach a point where you have to investigate,” Potter said.

The result was a trip to Virginia and Jamestown to learn as much as she could about these women. In addition to researching archives and libraries, Potter said she also “likes to see places on the ground. I visited as many places as we could find connected with these women.”

Helping her locally were historian Martha McCartney, now of Mathews County, Bly Straube, now senior curator of the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, and cultural historian Helen Rountree.

“I almost wrote the book for them,” Potter said. “But ultimately it was to be a book written by a woman, about brave young women with the help of three historians of today.”

Two of the 56 “Jamestown Brides” stand out for Potter — Ann Jackson and Catherine (Fisher) Finch. After arriving, Jackson went to Martin’s Hundred, a settlement east of Jamestown to join her bricklayer brother. Several months later, the Powhatans attacked settlements along the James River, including Martin’s Hundred.

She was captured and held captive for between four and six years, Potter wrote.

“Ann Jackson suffered three shocks: arriving in this strange and alien place, then in captivity by Indians and living within their culture and then coming back to the English society,” Potter explained.

Finch was 23 when she came to Jamestown, having been encouraged to go to Virginia by her brother, a crossbow maker to King James and later King Charles I.

“I visited the little church where she was baptized and found the grave of her brother. It’s amazing at the link between her home and Bermuda Hundred” where she lived.

“We know she married and had a daughter,” Potter explained, “and then went to Jordan’s Point. She then vanishes from history.”

Potter’s account of the brides also includes an amazing amount of early Jamestown and 16th century Virginia history. It should become an important new early colonial resource.

Have a comment or suggestion for Kale? Contact him at [email protected]