None of this history is new. Paul Kennedy admits as much in Victory at Sea, his new history of the Second World War’s naval struggles. Almost eighty years after that war’s end, it sometimes seems little remains to be written about the war at sea. Is another history needed? Kennedy’s genius has always been his ability to highlight how the shifting tectonic plates of power underlie and help explain the surface history, sometimes represented in a single event. Rather than uncovering new history, Victory at Sea arranges existing history in ways that better reveal the whole. Kennedy draws one connecting thread through the resources, strategies, and ends of each naval power, and explains the goals of battles and how they affected the war’s outcome. Such succinct and overarching analysis is rare, making the work a valuable addition. For those learning to connect military means to grand strategic outcomes, the book is required reading. The story of ONS-5 is the preeminent exception to an approach that generally eschews recounting the details of battle—though Kennedy wants to discuss its details so badly he describes them in the text and includes a further appendix on them. One reason perhaps, beyond its human tale, is that the battle captures so many of the larger book’s themes. It was one night that crystalized the full arrival of the Allies’ industrial and technological power.

As Kennedy outlines, the 1930s featured six major naval powers: the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Germany, and Italy. The Washington Conference’s Five Power Treaty had ensured the end of unilateral British naval dominance and established a relative hierarchy. Navies usually take time to build, and despite the treaty’s lapse, in many ways its pattern remained. The first three powers were clearly in a class above the last three, but all were of sufficient size that they could potentially shape the outcome of a conflict. In five short years, from 1939 to 1944, that multi-polar naval world would collapse to the unipolar naval world that with limited exception has remained unchallenged until the present.

Americans tend to focus on the Pacific war, acknowledge the Atlantic war, and mostly forget the Mediterranean war, except for its amphibious assaults. Kennedy places them in better balance.

The change occurred across the war in three separate theaters. First, the battle for control of the North Sea and the Atlantic that began with an Anglo-French alliance fighting Germany, transformed into a contest between Britain and Germany after the French surrender, and ended with the Anglo-American alliance’s eventual defeat of the Kriegsmarine. Second, there was the battle in the Mediterranean, where the fighting would occur principally between the British and the Italian Navy and German Air Force. And finally, there was the Pacific war with Japan, which would prove a mostly American affair.[5] Americans tend to focus on the Pacific war, acknowledge the Atlantic war, and mostly forget the Mediterranean war, except for its amphibious assaults. Kennedy places them in better balance.

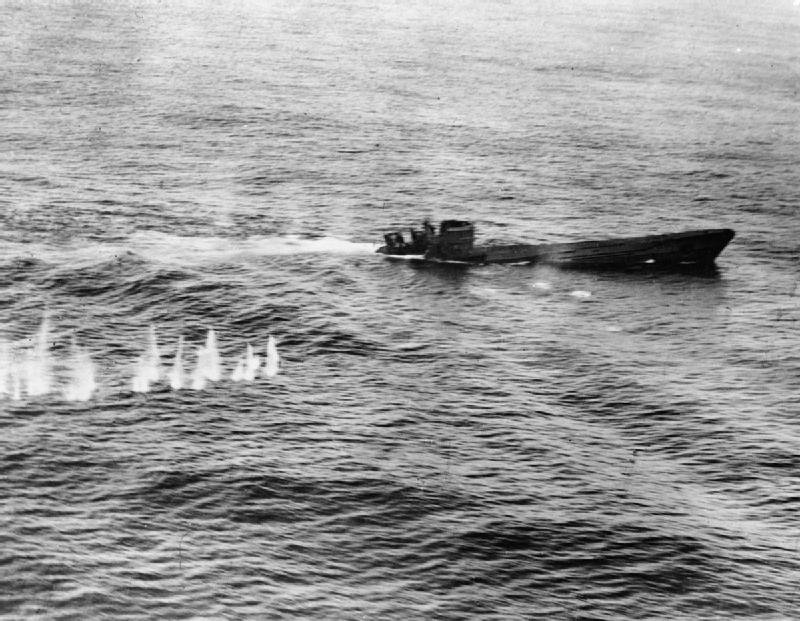

Similar themes emerge from his analysis across the three theaters. Victory at sea meant moving cargos across the sea to their destinations—not necessarily the destruction of enemy navies. This view has come to be called a Corbettian approach to sea control, but Mahan may have ultimately agreed—he would have most differed in believing the destruction of the enemy fleet was a prerequisite for moving cargo safely. Even if that had once been true, the maturing of both submarines and airplanes changed that dynamic.

The importance of airpower to sea control is not a new finding, but the regularity with which land-based air power—vice carrier-based—tipped or nearly tipped the balance becomes a consistent theme. The surprise with which this reality confronted many naval commanders early in the war is a potent reminder to refrain from discounting the influence long-range shore-based anti-ship missiles could have on naval conflicts today.

In two years, the Navy’s tonnage had more than quadrupled despite combat losses. Imagine today if the U.S. Navy built and trained crews for 800 ships in less than three years. At war’s end the United States Navy possessed almost twice as much naval tonnage as the remainder of the world’s navies combined.

More than anything else, the United States’ massive financial, technological, and industrial capacity—the tectonic plates of power distribution—shaped the outcome. The United States had begun a naval rearmament program in 1934 and supersized it as the war approached. Many of these ships and airplanes began to join the fleet in 1943. By whatever metric, ship count, ship tonnage, personnel, or aircraft; the U.S. Navy’s size exploded. In 1941, the U.S. Navy was roughly the size of the Royal Navy with warships that displaced just under two and half million tons. In 1943, the U.S. Navy displaced almost five and half million tons, and by 1944, 10 million tons, and growing. In two years, the Navy’s tonnage had more than quadrupled despite combat losses.[6] Imagine today if the U.S. Navy built and trained crews for 800 ships in less than three years. At war’s end the United States Navy possessed almost twice as much naval tonnage as the remainder of the world’s navies combined.[7] Britain had once maintained the two-power standard, the United States had achieved an all-power standard, and then some. All in less than 5 years. All without counting the similarly incredible construction of merchant ships. Even more incredible, had the U.S. Navy not existed in 1945, the Royal Navy alone would have been the “most powerful naval force the world had ever seen.”[8] Like a tsunami, this wave of Sailors, aircraft, and ships became almost unstoppable.